Today I remember the New Year’s Eve that we spent in remote Linyanti in Botswana’s Chobe National Park, as we anticipated the first year of this millennium. How different things are now.

Currently, here in South Africa a recently identified and more transmissible variant (different to the variant in the UK that evolved separately) impacts heavily on what was expected to be a festive season. Stricter regulations have been put in place at least until January 15th in an attempt to slow down the surging rate of infections as hospitals are already full. Unfortunately, we are not alone as the situation remains dire across the globe.

So I am thinking back (as I did last week) to what seemed the end of an epoch at the end of the millennium, but it is possible that we will recall this pandemic as being an even more decisive event, marking a significant change that we will feel for a long time to come.

Dawn of a new millennium, 1 January 2000, at Linyanti, Chobe National Park, Botswana

But despite surges in the pandemic, on the cusp of 2021 we are hoping for breakthrough events that will enable us to better manage the pandemic and restore our ability to be the social animals that we yearn to be without the fear of spreading infection.

But back at the end of 1999 as we entered the year 2000, my husband and I chose solitude under the splendour of the trees of the riverine woodland at the swampy edge of the Linyanti River. (All the photos in this post are scanned from old prints that were taken with pre-digital-era SLR cameras.)

The edge of the swampy margins of the Linyanti River near our campsite

The Linyanti River forms the border between Botswana and the Caprivi Strip region of Namibia. The river is part of a complex river system. The Kwando River, with its seasonal fluctuations in water levels, rises in Angola and flows through Namibia into Botswana and into the Linyanti Swamp near geological fault lines including the Linyanti Fault (which is associated with the Savuti Channel and the Silinda Spillway). The Linyanti River flows out from the swamp and as it flows east the river is renamed as the Chobe River.

Our campsite on the margins of the Linyanti River on New Year’s Day, 2000

The view from our campsite of a stretch of the Linyanti River with Namibia on the other side

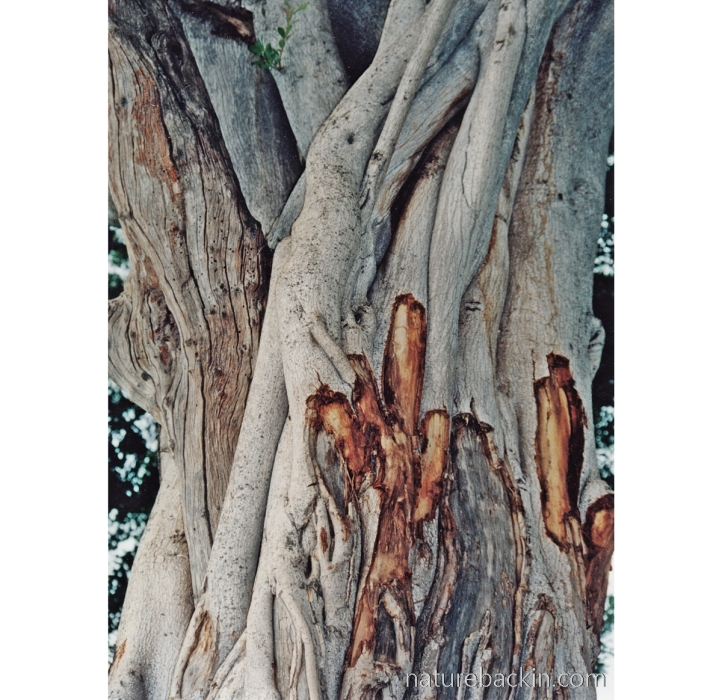

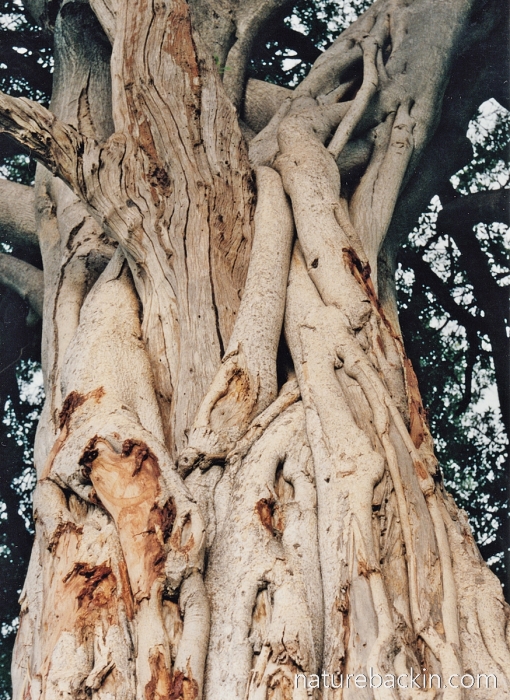

The riverine woodland includes many very large and beautiful trees such as jackal berry (Diospyros mespiliformis) and sycamore fig (Ficus sycamorus). Some of these old trees have a powerful presence that made me wonder if such trees do indeed exude some kind of energy field. Although as far as I have been able to find out, there is no such field measurable by science, humans can feel a kind of healing or even spiritual power from trees.

I think that this powerful tree is a jackal berry (Diospyros mespiliformis) but back then in 2000 although I really loved trees I was not that concerned about naming them!

More looking up and being awed by the strength and structure of a venerable tree

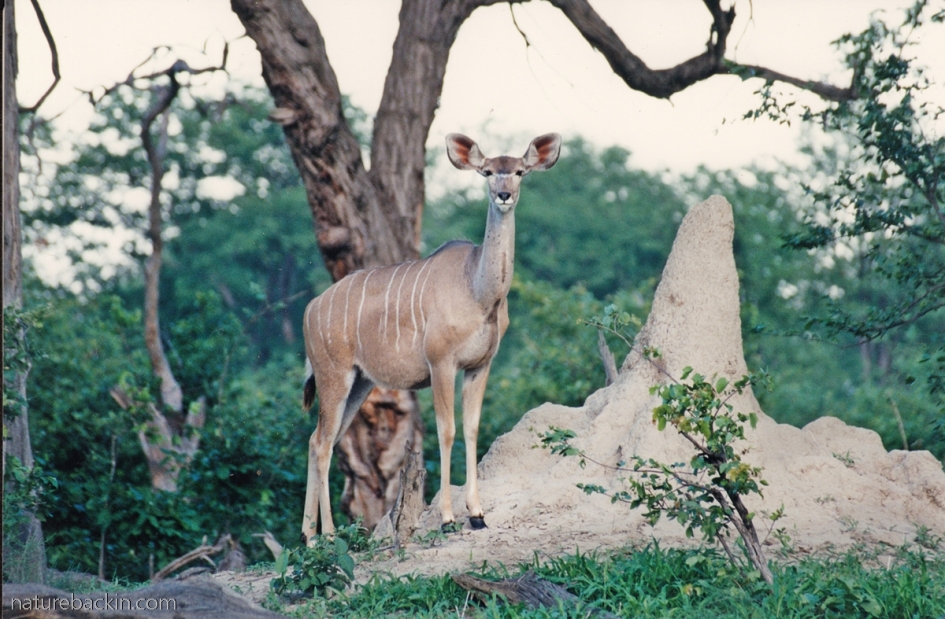

A kudu standing at a termite mound near the campsite. Jackal berry trees often grow on the rich and well-aerated soils of termite mounds

A view of the swampy Linyanti River beyond the large trunk of an old tree

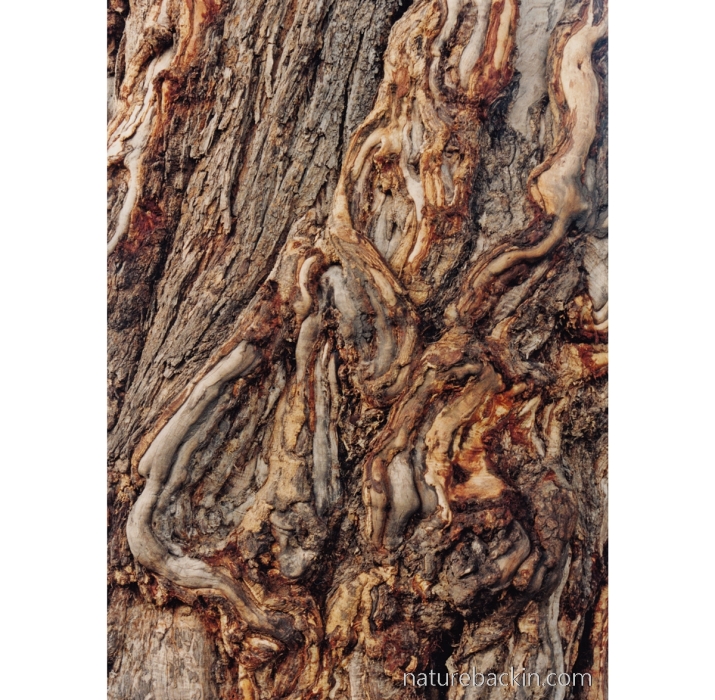

This tree shows scarring from being tusked by elephants

A large Sycamore fig (Ficus sycamorus) also showing scarring from elephant tusks

Another view of the sycamore fig and the signs of elephants tusking the bark. The memory of standing next to that powerful tree and its close association with elephants remains strong. I spent a long time in the company of that tree

Elephants are commonly considered to have a downside in that although they perform beneficial and necessary bush clearance, mitigating against the formation of dense thickets and maintaining open savannah, they can cause fatal damage even to large trees. In some areas, elephant are culled in the interest of protecting trees. Such practices have come in for criticism – see for example Debunking myths about the impact of elephants on large trees and another article discussing that elephants are only part of the story as in addition to the potential threat to trees posed by both elephants and fire other threats such as agriculture, climate change, commercial harvesting, disease and pests, exotic invasive species and human encroachment are relatively under-researched.

As I walked away from communing with the trees a small bee-eater flew by to land in reeds near the swampy edge of the river, so I crept down little by little to take this photograph. But was it worth it?

While creeping and crouching trying to photograph in the gathering dusk the bee-eater (which I think is an immature little bee-eater), I got chewed by increasing numbers of mosquitoes. Not wanting to frighten the bird I tried sweeping the mosquitoes off in slo-mo, being stupidly intent on getting a photograph!

Was it worth it? I don’t remember. On the way home I got sick and by the time I got home I had a shocking headache and was starting to get delirious with malaria. Of the next few days I remember very little. Without waiting for the test results (which turned out to be positive) the doctor prescribed Fansidar as a treatment for the malaria. The tablets took 24 hours to be delivered to the doctor’s consulting rooms (we do not live in a malaria area) and by the time treatment began, my husband says I was pretty sick with classic symptoms of malaria.

The doctor said it was just as well I had been taking a prophylactic medication as even though it is not 100 per cent effective in preventing against contracting malaria it does slow down the progression of the disease should one get it. Once the Fansidar kicked in it started relieving the fever and the delirium pretty quickly.

So was it worth getting malaria to take that photo? Even though there is much I don’t remember – on balance, I don’t think so!

The most festive sight that New Year was this red fire-ball lily (Scadoxus multiflorus), which was growing not far from our camp

And of course there was the dawning of a new day, a new century and a new millennium

This New Year’s Eve what we will have is a lit candle. As South African President Ramaphosa said in his recent address, he will light a candle at exactly midnight on New Year’s Eve in memory of those who have lost their lives and in tribute to those who are on the front line working to save our lives and protect us from harm. We are thinking that we will do the same.

Sources:

Harvey, Ross. 2019. Debunking myths about the impact of elephants on large trees. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/debunking-myths-about-the-impact-of-elephants-on-large-trees-122430; Nichols, CA, Vandewalle, ME, Alexander, KA. 2017. Emerging threats to dryland forest resources: elephants and fire are only part of the story. Forestry. An International Journal of Forest Research, 90 (4), pp. 4773-484. https://academic.oup.com/forestry/article/90/4/473/3076243;Team Africa Geographic. 2019. Elephants and trees. Africa Geographic. https://africageographic.com/stories/elephants-and-trees/

Posted by Carol

January 7, 2021 at 10:48 pm

What a frightening episode! My first reaction was yes, it was definitely worth it to catch that magnificent photo of the little bee eater. But the more I read on and heard about the consequences for you medically, the more I reasoned that it was probably not worth it for you. I certainly hope you are fully recovered.

The close-ups of the tusk damage on the trees or just incredible to see.

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 8, 2021 at 2:35 pm

Yes fully recovered thank you. I suppose it is possible I might have got it even if I had not taken the photo, but as I said I did take a lot of bites in the process and with hindsight I was foolish.

Yes there is something very intimate about seeing that tusk damage at such close quarters.

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 8, 2021 at 6:09 pm

Incredible…. on both counts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 7, 2021 at 5:17 pm

I’m so sorry to read about your bout with malaria at the end of such a beautiful trip, Carol.

We ALWAYS and RELIGIOUSLY use malaria prophylactic medicines when visiting areas where the disease is endemic, and so I was very surprised when I was actually admonished on one occasion by a clinic sister when I exhibited minor symptoms on return and wanted to be tested for malaria, as in her words the prophylactics “masks the infection and then you get a false negative result from the test and by the time your doctor figures out that you really do have malaria it is too late”. My surprise wasn’t at her gall for scalding a patient in need of assistance nor at a fallacy I hear repeated quite often, but the fact that such erroneous beliefs even circulate in medical circles had me absolutely confounded.

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 7, 2021 at 8:10 pm

Yes we are careful too to take a prophylactic when necessary too (although I did have a bit of an unpleasant time on Lariam quite some time back).

Your story about the admonishing clinic sister and that she believed that story about prophylactics masking infection is shocking. What hope for the rest of us if medical people can be so ill-informed! I generally don’t tell people we take prophylactics as I get tired of that erroneous advice given so freely and forcefully! Who wants to improve their chances of cerebral malaria!

I hope that you did get the assistance you needed in the end and that in fact you did not have malaria.

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 5, 2021 at 9:15 pm

I can well imagine that you have mixed feelings looking at the bee eater photo now! I had a positive malaria test many years ago when I was travelling in India but it was one of the milder variants. Interestingly, the Oxford team behind one of the covid vaccines are in the final stages of testing a malaria one. Maybe those foul-tasting anti malarials will one day be a thing of the past.

It’s fascinating to see the elephant tusk scars. Around here, I see rubbings where our little roe deer have marked their territory with a scent gland on their heads, but these are on a different scale!

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 7, 2021 at 7:40 pm

I have read a bit about the malaria vaccine that is in development. I wonder if funding has been diverted more towards Covid research given the urgency of the pandemic – although of course the number of people dying from malaria, at least in many African countries, is high.

Yes those large trees marked by elephants I found strangely mesmerizing. I assume they tusk trees both to mark territory and to sharpen tusks. Of course they also strip off bark to eat.

Like your roe deer we see lots of markings on tree trunks here from bushbucks in our neighbourhood.

LikeLike

January 1, 2021 at 11:28 am

As it turns out, this might have ben a very suitable adventure for this time of Covid – provided you took a supply of malaria drugs with you. That sounds very nasty indeed. But you seem to have enough memories, and photos, of what was clearly a memorable time. All best wishes for 2021, from one beleaguered country to another.

LikeLiked by 2 people

January 1, 2021 at 7:19 pm

I’m afraid that Covid has shut down our desire to travel – it seems unfair to risk being a spreader as well as risking infection, even if such travel across borders were possible. Yes our respective countries do seem to be particularly beleaguered currently. Let’s hope that the majority of people do take the need to take precautions seriously – if only for the sake of our health workers and hospitals, although also of course for ourselves and each other. Best wishes to you too, and may the pandemic be turning a corner for the better as the year progresses.

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 2, 2021 at 8:46 am

We can only hope…

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 1, 2021 at 10:58 am

I loved reading your post, and seeing photos of some of those magnificent trees, especially the ones showing the gouges made by the elephant tusks. I believe we have one case in quarantine that has the South African variant of the virus. Wishing you all the very best for the new year. May you stay safe.

LikeLiked by 2 people

January 1, 2021 at 7:15 pm

Thanks, I enjoyed sharing these old pics and reminiscing about that trip. I hope the person carrying the SA variant has been quarantined in time, but sadly it seems the variant in the UK and the variant here are making their way out to other countries. May you stay safe too and best wishes for the year ahead.

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 1, 2021 at 8:20 pm

After reading your post I sat down with my hard drive of photos and did some reminiscing myself! It was great! Yes, the person was an overseas arrival and in mandatory quarantine at the time, so here’s hoping it does not spread further. Thanks for the good wishes!

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 3, 2021 at 1:52 pm

Glad that you also took the time to do some pleasant reminiscing 🙂

I do hope that the spread of the variant is successfully contained.

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 1, 2021 at 9:05 am

Thank you for reminding me of the beauty and grandeur of trees. The photograph of the bee-eater is spectacular, so it was worth it for us viewers, so thank you for risking your life to take it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

January 1, 2021 at 7:13 pm

Thanks Mariss – there is something incredibly therapeutic and powerful about such trees. As for the bee-eater photo, I should have known better but did not think about it being risky at the time 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 1, 2021 at 7:21 am

Dear Carol I love your posts of wild camping trips in the past. Your tree photos are so very evocative, I stand in awe when I’m out there near them, so a good memory trigger, thank you! May the beauty that surrounds us every day be the guiding star this new year. Much love, xxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 1, 2021 at 7:11 pm

Dear Christeen – I enjoyed revisiting this trip and such trees are powerful even in memory. Lovely that we have shared memories of the power of trees. I really like the idea of letting the beauty of nature be our guide – we do need to be more observant and responsive to it going forward. Love to you too xxx

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 1, 2021 at 6:13 am

Beautiful post of a wonderful trip. I looooove the huge trees. My heart aches when I think of the deforestation happening globally. A very large chunk of what’s happening regarding climate change is directly related to animal agriculture. I am considering my diet and the changes that need to be made. So that my great grandchildren get to see giant trees like the ones in your post.

Thanks for sharing. ❤️🌳

A very blessed New Year to you all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 1, 2021 at 7:07 pm

Thanks Debbie those big old trees are wondrous. The extent of deforestation is astonishing, and it is true that it can all to often be connected to agriculture and things like cattle ranching. I agree about the need to think more about what we eat and try to learn more about the sources of our food, although it is not always easy to find the information we need. We do have a responsibility though to ourselves, to the planet and to the next generations. Hoping that we all hasten our learning as we go into this New Year. Best to you too.

LikeLike

January 1, 2021 at 5:39 am

Balm for the soul – that is what this post is. How refreshing to read of an adventure in a beautiful place in the past, reminding us of the value nature has for those who care to turn to it. Trees have properties that we may well understand more fully – we filled our desert-like garden with trees three decades ago and are reaping benefits from them now. I look forward to reading more of your writing as this year unfolds.

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 1, 2021 at 11:28 am

Hi Anne, I am glad this post struck a chord with you as we remember times past in nature. It is astonishing what a difference trees make to a space and wonderful that you have been able to stay long enough in the same place to see the trees you planted come into their own. We are benefitting from the plantings done by the previous owners of our house, in addition to adding a few more ourselves. Trees add another dimension quite literally as well as altering the the atmosphere of a space.

I hope you enjoy another year of productive and interesting blogging and it has been great to meet you and to interact and compare notes via our blogs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 1, 2021 at 4:24 am

Great photos of the trees. They have such character. The bee-eater is a lovely photo, but I’m not sure it’s worth getting malaria for it. For that I think it would need to be at least an eagle locked in battle with a hippo or some such thing. Do you have any lingering effects from the malaria?

I didn’t realize your covid variant was different from the UK one. It does seem to be a very adaptable virus. I hope you stay safe, have a good new year, and look forward to a much better 2021.

LikeLiked by 2 people

January 1, 2021 at 11:17 am

Yes I agree that trees can have such character. I am not sure that even the drama you envisage is worth getting malaria for 🙂 The type of malaria that occurs in the region is not the kind that reoccurs, thank goodness.

It is interesting that two different variants of Covid arose in different countries towards the end of the year, and that what they have in common is that they both seem to be more transmissible.

We are trying to stay safe, and I hope that you stay safe too, and lets hope things will improve during the course of the year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 1, 2021 at 11:52 pm

Glad to hear your malaria was a one off, but still not a fun experience I’m sure. Things are OK here though I’m dragging today after the barrage of fireworks in the neighborhood last night!

LikeLike

January 1, 2021 at 3:05 am

I may be a bit behind the times with our different time zones? but nevertheless I’m here to wish you a very happy and healthy new year!

Your comparison to the beginning of your millennium was delightful. Mine was quite different. I think I prefer yours by far. Funny how both of our 2021 posts featured large, impressive, indigenous trees. They really are such incredible wonders. It baffles me that we humans can’t seem to do more to protect and preserve these marvels. I suspect that it certainly isn’t the elephants’ fault. As here scientists are becoming concerned about our redwoods being struck because of climate change. We’re already seeing dye-off of large numbers of trees attacked by disease in one way or other. The trees are also stressed because of the droughts along our western coast.

Your bee-eater looks so cute, and similar to our hummingbirds, but with a much shorter beak. Oh but…. I’m not sure the photograph was truly worth getting malaria. It’s such a sweet picture it’s a pity it is associated with such unpleasantness!

I like the thought of lighting a candle for those lost this past year. I’ll need to remember to do that if I’m still awake.

Wishing you a happy new year and one to make far better memories in the coming year!!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

January 1, 2021 at 7:34 pm

Dear Gunta – yes indeed it is a coincidence that our posts both centred around grand old indigenous trees. The dying off of woodlands and forests in so many regions of the world is alarming and sad.

Yup it was silly of me to persevere taking that photo no matter how sweet the little bird was. I was very disappointed in the photo at the time.

Lighting a candle in remembrance and tribute I found much more meaningful than the noisy explosions of fireworks that some in our neighbourhood were deploying on New Year’s Eve.

Yes I wish the same for you for the coming year – and I hope that you remain safe and inspired and comforted by nature in your beautiful part of the world.

LikeLike

December 31, 2020 at 10:43 pm

A terrible consequence! Do you have lingering effects from the disease?

Hindsight is 20/20, as they say, and I wonder what we will think in another decade or two about this year? May we live to tell the tale. Stay safe and well, Carol.

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 1, 2021 at 11:07 am

Thanks Eliza. The type of malaria that is prevalent in the southern African region is not of the type that can reoccur, luckily for me in this case.

Yes it will be interesting to know how the pandemic is viewed in a decade or so, It is incredible that the 1918 flu, which was far more devastating in terms of the number of deaths alone, was somehow overshadowed in the history books at least by the world wars and the Great Depression.

WIth very best wishes and you keep safe and well too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

December 31, 2020 at 9:52 pm

Sending you warm wishes for 2021, Carol. Stay safe. Be well!

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 1, 2021 at 10:53 am

Thank you very much Sandy, and I wish the same for you in the year ahead. Take care.

LikeLiked by 1 person

December 31, 2020 at 9:46 pm

A fascinating post, Carol. I was interested to learn about elephants tusking trees, and I loved the photo of the bee eater, but commiserate with you on the drastic effects of the mosquito bites. Does that episode mean that you will continue to suffer bouts of malaria in the future?

I wish you all the best for 2021, and stay well!

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 1, 2021 at 11:00 am

Thanks you very much Jane. Fortunately the type of malaria that is prevalent in the region is not the type that can reoccur.

Sending best wishes to you too for the year ahead, and let’s hope that the pandemic can be better managed in the months ahead.

LikeLiked by 1 person