The appealing Wood Owl is one of the species of raptors that occur in our neighbourhood. Raptors are generally beneficial to us humans because they prey on species that, if their numbers get out of hand, can become problematic to us, in both urban and rural settings.

Rats can become a health risk if they are disease carriers, and they can be a problem where food is stored. Some even gnaw on electrical house wiring. In South Africa, generally rats and mice that are problematic are introduced species. The Urban Raptor Project, based in Port Elizabeth, identifies the three species of introduced rodents as: the Norwegian/brown rat (Rattus norvegicus), the black/house/roof rat (Rattus rattus) and the house mouse (Mus musculus).

Natural predators of rats and mice include many species of raptors and small carnivores. Also several species of snake predate on rodents.

In suburban areas in South Africa, the Brown House Snake can be a beneficial presence, such as this one sunning itself in our garden on an unseasonably hot winter’s day. Brown House Snakes are constrictors and have no fangs and are not venomous

It is ironic that many of the predators that can help control populations of potentially problem animals, are themselves targeted by us humans for eradication, often deliberately. In addition, many die as “collateral damage”; that is their deaths are secondary to the target species.

In South Africa, as elsewhere, the list of routinely killed animals and birds, which if allowed to survive could assist us in controlling populations of rodents and other potentially nuisance animals, is long. It includes raptors – large and small, snakes, Wild Dogs, Caracals, species of mongoose, jackal and genet, as well as indigenous rodents that are seldom a problem, among others. And this list does not include the numerous non-target species that also die in traps and from poisons.

Although we often hear a pair Spotted Eagle Owls and a pair of Wood Owls calling in our garden at night, I have not even tried to photograph them. This photograph was taken during this Spotted Eagle Owl’s flying display at the African Bird of Prey Sanctuary in KwaZulu-Natal. Although owls are deliberately targeted for killing by some people, just as lethal for owls is secondary poisoning, commonly from rat poison that they ingest from eating poisoned rodents

Recently, someone told me that secondary poisoning by rat poison (rodenticides) is not an issue for raptors as they do not eat dead animals. As this view did not tally with what I understood to be the case, I decided to read further about the risks that rat poisons pose to raptors and other wild animals, with a view to writing this post. What I found was far more sobering than I anticipated, but we must not lose sight of the fact that reducing the use of rat poisons and helping to raise awareness of the consequences of its use is something that we all can do. I hope that this post helps us understand a little more as to why rat poisons should not be used.

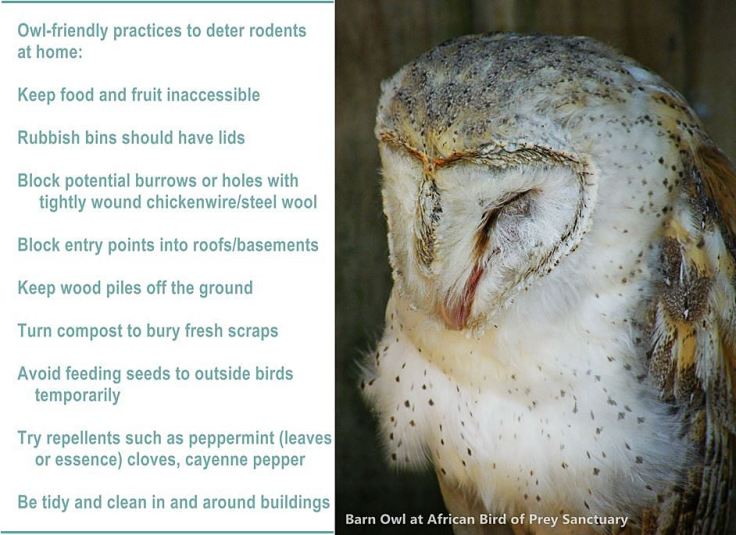

Rat infestations in urban and suburban areas tend to go hand-in-hand with poor waste management as rats thrive on scavenging easy-to-find food. A major step towards controlling rat infestations would be to minimise waste, especially food and food residues, and remove or make inaccessible unavoidable waste. The same applies in our homes. Unfortunately, even these simple steps towards discouraging rats are often overlooked as using rodenticides, which seem to be regarded as a kind of panacea, is seen to be an easy option.

When the first returning migrant Yellow Billed Kites are seen in our skies in springtime, we know that winter is over. The Yellow Billed Kite’s diet includes small vertebrates and carrion. Its eating habits and the fact that it confidently hunts and scavenges in towns and villages puts it at high risk of poisoning by rodenticides. This photograph is of a rescued bird at the African Bird of Prey Sanctuary

There are several types of poisons used as rodenticides. In this post, I focus on the commonly used anti-coagulants, which thin the blood and prevent it from clotting so that poisoned animals die from internal bleeding. How long this takes, depends on the poison used, the amount consumed relative to the size of the animal, and the species-specific metabolism.

According to the United Kingdom-based Barn Owl Trust, after eating poisoned bait the time it takes for a rodent to die varies from 2 to 12 days. In some cases, an individual may not ingest enough poison to kill it (a sub-lethal dose) and continues living, carrying poison residues in the liver. Poisoned rodents that are weakened from chronic exposure or that are dying from ingesting lethal amounts are sluggish and make easy prey for raptors and other predators. In fact their easy capture can lead to poisoned animals forming an increasing proportion of the diet of predators, including owls. Raptors and carnivores eating poisoned prey suffer secondary poisoning that can cause a slow and painful death, or else the animal survives, although weakened, carrying a residue of poison in its body.

Direct deaths from rodenticides of non-target animals and birds from many different species have been recorded worldwide. The Barn Owl Trust reports that typically it takes 6 to 17 days for a Barn Owl to die after eating 3 mice containing the poison Brodifacoum, which is one of the second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides first developed in the 1970s, after rodents were showing signs of becoming resistant to first-generation anticoagulants. The Barn Owl Trust has a clear explanation of the various rodenticides here, and the Wikipedia entry on rodenticides has a useful table, see here.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency in the United States, second-generation anticoagulants are more likely to be able to kill after a single night’s feeding. Although the time taken for the rodent to die is similar to those poisoned by first-generation compounds that require several feeds, the compounds tend to remain in animal tissues longer than do first-generation ones, posing a greater risk to non-target species. Brodifacoum is one of the particularly high-risk poisons for non-target species, both raptors and mammals.

Non-target secondary poisoning commonly includes many species of raptor, including endangered species. Secondary poisoning also affects many mammals, such as those in the United States listed in this extract from a 2013 article in the Audubon Magazine (Williams, 2013).

“There’s no safe place or safe delivery system for second-generation rodenticides. After a rodent partakes, it stumbles around for three to four days, displaying itself as an especially tempting meal not just for raptors but for mammalian predators, including red foxes, gray foxes, endangered San Joaquin kit foxes, swift foxes, coyotes, wolves, raccoons, black bears, skunks, badgers, mountain lions, bobcats, fishers, dogs, and house cats—all of which suffer lethal and sublethal secondary poisoning from eating rodents. Deer, nontarget rodents, waterfowl, waterbirds, shorebirds, songbirds, and children suffer lethal and sublethal poisoning from eating bait directly.”

Small carnivores, such as mongooses, genets and Caracal, are vulnerable to secondary poisoning from rat poisons. This Slender Mongoose lives in our neighbourhood and I photographed it at the bottom of our garden

And what about the low levels of chronic exposure occurring in individuals that have not received a lethal dose? Animals and birds surviving with chronic secondary poisoning are at ongoing risk of ingesting more poisoned animals, accumulating more toxins over time. And in turn, they may be eaten by other creatures and so the poisons accumulate higher up in the food chain. This process of bioaccumulation is so extensive that numerous species, including those that do not eat rodents, have detectable amounts of rodenticides in their bodies.

Researchers are still investigating the effects of chronic low-level exposure to rodenticides on individual animals. For a detailed list of the health impacts on animals and birds weakened by chronic exposure to rat poisons, see here.

As an example of the effect of chronic exposure to anticoagulants, a study in the United States found a direct link between poison exposure and notoedric mange in bobcats. For details see this article by Laurel Serieys. The hair loss and emaciation resulting from the mange usually proves fatal, possibly related to the immune dysfunction that occurs as a result of exposure to the poisons. Such weakened animals are also vulnerable to being killed by cars. The study reports on two fetal bobcats from mothers killed by cars that were tested, and even before they were born, detectable exposure to rodenticides was found in the fetuses. In southern California, 92% of bobcats tested from samples collected between 1996 and 2012, were found to have been exposed to anticoagulants. And in New York, 49% of predatory birds tested from 1998 to 2001 were positive for anticoagulants.

Laurel Serieys, when working in South Africa for the Cape Leopard Trust as Urban Caracal Project Coordinator, tested one genet and seven caracal (all road kills) in the Western Cape, and found that all were exposed to rodenticides, with all seven caracal showing exposure to compounds from three different anticoagulant rat poisons. For details see here.

In a broader study involving analysis of the livers of 401 wild and domestic animals found dead in Spain, 40.9% were confirmed poisonings, and of these 21.1% involved anticoagulant rodenticides (AR). Grain-eating birds showed the highest prevalence of primary AR exposure (51%); that is they ate poisoned bait. Secondary exposure was high in nocturnal raptors (62%) and carnivore mammals (38%). See the 2012 abstract of the study here.

I asked a vet at a local veterinary practice, and there are many practices in this region, how many cases of pets poisoned by rodenticides are brought into his practice. He checked his records and told me that his practice has had on average 13 confirmed cases of poisoning by rodenticides per year, each year over the last 3 years. Of these, all were dogs, except one, which was a cat. This number, working out at just over one a month, is quite high given that this is just one practice out of many, and not all poisoning cases are taken to a vet. For one thing, and this is speculation, some poison victims, especially cats, just don’t make it home.

One of the raptors that is fairly common in suburban areas, including ours, is the African Goshawk. This one was photographed during its flight display at the African Bird of Prey Centre

There is an argument that first-generation anticoagulant rodenticides are better to use than second-generation ones. This is only relatively true and does not mean it is safe. It is still a poison. Recommending its use generally ignores the problem of non-lethal chronic exposure, which is not widely known about and the ongoing implications are not fully understood.

Adverse effects of first-generation anticoagulants such as coumatetralyl (the poison used in Racumin, which is actively promoted as a “safe” poison) include primary and indiscriminate poisoning of non-target species of small mammals. A 2005 study in the United Kingdom, where coumatetralyl was used, by Brakes and Smith (see here) found that the eradication of non-target small mammals, such as woodmice and voles, can lead to malnourishment and starvation among predators such as weasels, stoats and owls, and this is in addition to the adverse effects of secondary poisoning. It is noted in the same study that sub-lethal secondary poisoning does significantly weaken the mobility and fitness of affected birds and animals.

As Tammy Caine, Clinic Manager at Raptor Rescue in KwaZulu-Natal told me: “a sick raptor is often a dead raptor. The accumulation of the poison will undoubtedly make the raptor feel ill, and negatively affect its ability to hunt, leading to starvation, a compromised immune system and eventual death. No poison is safe. Period.”

After all this sobering information, it is good to know that there are methods and projects that follow non-toxic practices. Here are just three in South Africa.

One of Raptor Rescue’s projects is the Owl Box Project, a pilot project run under Predatory Bird Projects and supported by the N3 Toll Concession. The project instigates and oversees the installation of owl boxes in both urban and rural communities and encourages the protection and conservation of owls in these areas as part of environmentally friendly pest control management. In addition, the project collects comprehensive data to aid future research on urban/rural owl population dynamics. The project has supported educational outreach in rural areas, particularly targeting schools, to encourage active participation and interest in owl conservation. For more information on this project see https://www.facebook.com/owlboxproject, and for Raptor Rescue’s other projects see here.

The Urban Raptor Project in Port Elizabeth in the Eastern Cape, is involved in numerous conservation projects. It has a successful rodent control project, using carefully monitored spring traps, as well as establishing owls (they have their own owl breeding programme) and other predators in poison-free areas. They also use Rat, English Fox and Jack Russell terriers as a traditional form of rodent control. Among other places, they manage the Nelson Mandela Metro 2010 World Cup Stadium and the Port of Ngqura. They actively encourage the protection of indigenous rodents. Their website provides a wealth of information. See here.

The Township Owl Box Project run by EcoSolutions Pest Management Specialists with support from the Roots and Shoots programme under the auspices of Dr Jane Goodall, as well as the Gauteng Department of Agricultural and Rural Development, through a process of education and finding suitable school properties in townships in Gauteng, is able to introduce orphaned owls into these areas. The school children benefit from learning about and taking responsibility for the owls, the orphaned owls benefit as they are released into a managed environment, and the community benefits as the owls provide a poison-free form of rodent control. For more information see here.

A Spotted Eagle Owl, one of the commonest owls in South Africa, at the African Bird of Prey Sanctuary

Non-toxic rat traps

For serious rat infestations, lethal methods of control may be necessary. Generally, rodents gain little sympathy, but they are intelligent creatures and like any other animals, surely they should be spared the terrible suffering caused by rodenticides.

The spring trap is well known, and has a place if used correctly and monitored properly. It should never be placed outside or in an area where it can trap non-target species.

Here are three other non-toxic devices:

Electronic Rat Killers are walk-in traps that electrocute the target. These traps provide a humane and environmentally friendly way of eradicating problem rodents. One brand is known as Rat Zapper. For a description see here, and for a South African supplier see here.

Nooski Trap System shoots a latex ring around the neck or chest of a rodent entering the trap and kills the rodent within seconds – a lot quicker than the many days it takes for a rat to die from anticoagulant poisons, and with no poison used, no secondary poisoning is possible, but as with all traps it should be monitored, and dead rats disposed of safely. In the case of this trap, the killed rodents will each have a latex ring around their necks. For a description of how it works, see here. I was able to find only one South African (online) supplier here and would be interested to know if anyone has found it sold at any other outlets.

Live capture traps. Such traps need to be set preferably indoors in areas where rodents are a problem, and must be monitored regularly. Where appropriate, rodents that have not been exposed to poisons can be released in areas where raptors and other predators can hunt them, or else they can be killed using a humane and non-toxic method. See such traps at Radical Raptors here.

So what can we do?

The first step is to be aware and actively try to be informed about the hazards of rodenticides as well as related regulations and legislation. Such awareness would likely make us pledge never to use rat poisons at home or in our neighbourhood. Perhaps we can use our awareness and some of the excellent information resources available to persuade organisations that we know use rodenticides, such as our places of work or shopping centres, to find alternative methods. We can also interrogate pest control companies that claim to be environmentally friendly to find out what methods and compounds they actually do use in their rat control programmes.

Perhaps information and awareness will lead people and organisations to shift away from the use of poisons, and so in time we won’t be reading stories such as this in our local newspapers or social media.

It is not known if this Crowned Eagle died of secondary poisoning or if it was deliberately poisoned. What is known is that it died a slow and painful death from ruptured internal organs and extensive internal haemorrhaging. Surely incidents such as these motivate us not to use rat poisons?

Crowned Eagles, the second-largest eagle in southern Africa, survive in game reserves, forest patches and in plantations even on the edge of towns and suburban areas. Their main prey animals are Vervet Monkeys, dassies (Rock Hyrax) and small antelope. It is disturbing to know that they are also falling victim to rodenticides. The individual in the photographs above is at the African Bird of Prey Centre. It was found on the side of a road with a badly broken wing and toe. Although its injuries have healed, it is not strong enough to be able to hunt successfully in the wild and so cannot be released

A resident pair of Crowned Eagles as we usually see them in our neighbourhood. Flying high and free

Information sources and further reading:

African Bird of Prey Sanctuary. “Owl-Friendly” Rodent Control http://africanraptor.co.za/?page_id=4100

Barn Owl Trust http://www.barnowltrust.org.uk/hazards-solutions/rodenticides/background-rat-poison-problem/

Brakes, C.R. & Smith, R.H. 2005. Exposure of non-target small mammals to rodenticides: Short-term effects, recovery and implications for secondary poisoning. Journal of Applied Ecology, 42(1): pp. 118-128. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2005.00997.x/full

Endangered Wildlife Trust: Birds of Prey Programme. Eagles and Farmers https://www.ewt.org.za/eBooks/booklets/Eagles%20and%20Farmers%20booklet.pdf

Raptors are the Solution http://www.raptorsarethesolution.org/

Raptors are the Solution. Rat poisons not only kill wildlife, they can also weaken and sicken them. http://www.raptorsarethesolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/RATS-fact-sheet-on-sublethal-impacts.pdf

Serieys, Laurel. 2015. Rat Poisons Kill More than Just Rats , in Game Changers by Jean Dunn. http://lifeinbalance.co.za/rat-poisons-kill-more-than-just-rats/

Serieys, Laurel. Why Do Poisons Matter? http://www.urbancarnivores.com/poisons/

Sanchez-Barbudo, P.R. Camerero & R. Mateo. 2012. Primary and secondary poisoning by anticoagulant rodenticides of non-target animals in Spain. (Abstract). Science of the Total Environment, 420: pp.280-288. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S004896971200071X

Township Owl Box Project. http://ecosolutions.co.za/giving-back/township-owl-box-project

Wikipedia. 2017. Rodenticides. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rodenticide

Williams, Ted. 2013. Poisons used to kill rodents have safer alternatives: A second generation of ultra-potent rodenticides creates a first-class crisis for people, pets, and wildlife. http://www.audubon.org/magazine/january-february-2013/poisons-used-kill-rodents-have-safer

Urban Raptor Project. http://www.urbanraptorproject.co.za/index.html

Posted by Carol

May 16, 2017 at 5:22 am

I think the more you know about this topic the less likely you are to leave out poisons. It’s one of those things that once you are made aware of the consequences of your actions you come up with another solution.

LikeLike

May 16, 2017 at 6:18 am

Thanks for your thoughtful comment. I very much hope that this is the case.

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 13, 2017 at 12:47 am

Thank you for sharing – that was very informative – those animals are beautiful and it’s terrible that we are poisoning them but there must be a better way of reducing the rodent population without endangering other species. Thank you for the information – very enlightening Carol !

LikeLike

May 13, 2017 at 12:50 am

PS. would I be able to use your first Owl picture? It’s beautiful! Not related to this subject – I can be reached at https://professionalshealthconnection.com – thank you!

LikeLike

May 13, 2017 at 8:10 am

Thanks Joan. I learnt a lot when reading for this post. The widespread effects of poisons are horrific, but there are alternatives available.

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 12, 2017 at 1:57 pm

This is a well-timed post. My sister (in Boston, Massachusetts) is dealing with a rather large rat infestation caused by the bad habits of her neighbors. Apparently my brother-in-law has turned into Bill Murray in the movie Caddyshack (have you seen it?) and is just obsessed with getting rid of them. I believe he’s used all of the means you mentioned, in addition to his own cat and a bb gun he now keeps by his bed. (That trap with the electricity seemed medieval when my sister mentioned it, but now I can see its humane aspects). They’ve not resorted to poison or an exterminator. I’ll forward this to be sure they never do!

LikeLike

May 12, 2017 at 4:29 pm

Great that this post is timely. I love Bill Murray but have not seen Caddyshack. Regarding the electronic killer, of the options I came across it does seem to be the most humane, as death is instant. It should be set where unintended targets won’t be trapped, and the bodies need to be disposed of safely – preferably buried I would guess. I will be interested to know if they try this option and if it is successful. A shame that the neighbours’ habits are causing this problem in the first place.

LikeLike

May 12, 2017 at 4:43 pm

So far the housecat has been the most successful, but they need to leave the basement for him to get them, which is not ideal. I’ll have to ask for an update on the new traps.

LikeLike

May 12, 2017 at 8:31 pm

I hope they are able to work something out.

LikeLike

May 12, 2017 at 9:53 am

The problem with rat poison and birds of prey is world wide. We have the same problem in Central; Park, NYC

LikeLike

May 12, 2017 at 3:32 pm

Thanks Sherry. Sadly yes, it is a worldwide problem and so many species are killed directly or through secondary poisoning, or become sick through chronic exposure.

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 12, 2017 at 7:53 am

Superb post, Carol.

We occasionally come across a rat or mouse here in Observatory. I suspect,due in no small part, to the nearby suburb of Yeoville, which has suffered serious urban decay over the past decade, and all the ensuing problems that result.

I never ever poison anything and am as careful as one can be when recycling household waste, especially foodstuff, all of it being kept in a tightly sealed plastic bin until it is ready for use as compost

We have cats that seem to keep most rodents at bay, ( one assumes they do as I very rarely see any) but I have never considered the possibility of neighbours putting down poison and I know a number do not have cats or dogs. I shall make inquiries.

I came face to face with a rat in my garage a few years ago. At that stage we had twenty cats and my initial thought at the time was: If you managed to evade all twenty than who am I to stand in your way Mr Ratty? So I stood aside and he fled. Never seen a live rat since.

LikeLike

May 12, 2017 at 9:35 am

Thank you Ark. The effects of urban decay are sad and multiple. It is troubling that despite anyone’s best efforts these can be undermined by other practices in the neighbourhood. Let us hope that raising awareness can reduce the use of poisons, including also pesticides.

I love your story of Mr Ratty. (I am forever indebted to “The WInd in the Willows”.) The most cats we have had at one time is nine – all rescued and greatly loved, and we thought that was a lot! I can’t imagine having twenty – how amazing! We have enclosed part of our garden on two sides of our house with a cat-proof fence to restrict our cats from hunting and it also serves to keep them safe too.

LikeLike

May 12, 2017 at 10:15 am

The most cats we had at one time was 23. We have not actively replenished the stock as they inevitably succumbed to old age or illness. We currently have four and the neighbour’s cat, Ginger,which makes sort of 5, who seems to have adopted us, much to the chagrin of one of the females Kammy.

Except for Kammy, ours don’t seem to hunt these days, preferring to sleep most of the time in a warm sunny spot.

Kammy will go after the odd mouse or rat(if we see one) and the lizards, which frequent our spot.

As is the cat’s wont to bring their prize home, most we manage to rescue, thank goodness.

LikeLike

May 12, 2017 at 3:26 pm

We also have four cats. Of these three of them (all different ages) were brought to my husband on separate occasions as dehydrated orphans only a few days old, and we managed to hand-rear all three, so our relationships with them is very special, as you can imagine. The fourth, now 17 years old, was rescued when about five weeks old, after calling for his mother continually for over 8 hours. The mother and siblings were never found.

Thank you for reblogging my post on rat poisons. The more people who are aware of the dangers, and that there are alternatives, the better for us and our wildlife.

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 12, 2017 at 12:56 am

Great post – well researched and your alternatives make so much more sense. While I’ve never had a rat problem, thankfully, we do have mice. Desiccants are widely sold, but I would never buy any for the same reasons you state. One must think of the food chain in its entirety.

LikeLike

May 12, 2017 at 5:30 am

Thanks very much Eliza. I so agree that we should try to be mindful of the bigger picture.

LikeLike

May 11, 2017 at 8:21 pm

A well researched, interesting and pertinent article as always. I am always pleased to spot the grey mongoose and even the odd snake in our garden for they are natural rodent controllers.

LikeLike

May 11, 2017 at 9:38 pm

Thanks Anne. I wish more people would appreciate and not harm such creatures.

LikeLike

May 11, 2017 at 6:09 pm

As a postscript. My last cat died of rat poisoning. He is the last cat I will ever own because his death was absolutely distressing in the extreme

LikeLike

May 11, 2017 at 7:09 pm

I am very saddened to know about this. So hard to bear and I understand your decision. When reading for this post I read about the most appalling suffering.

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 12, 2017 at 7:55 am

It was nearly 11 years ago and I still can’t bear to think about it. I can only imagine the ghastly things you read. And for that reason I can’t condone rat poison under any circumstances. Thank you for your kind words.

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 12, 2017 at 9:21 am

As I write this a few young monkeys are playing outside my window. Two weeks ago four monkeys were poisoned in a nearby suburb, and there were other recent cases of multiple poisonings of monkeys in suburban areas in the province. These monkeys are not threatening anyone’s livelihood. They are deliberately killed because they are regarded by some as a nuisance or irritation. Why we cannot find ways of adapting to living alongside these animals and how in the face of our inhumanity we can continue to think we are intellectually superior beats me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 12, 2017 at 11:11 am

That is absolutely dreadful. I fail to understand manUNkind’s inability to co-exist. And what happens? All of a sudden he realises that, for example, bees are vital to OUR survival and all hell breaks loose as we try to fix the mess we have made in virtually wiping them out. Live and let live and allow all species to coexist peacefully would be so much more wise as well as decent. By the way, my mother, in her farther chi-chi cul-de-sac in Oxfordshire has a rat in the garden. Her neighbours implore her to put poison down and she refuses. He gardener suggested it and she said she would sack him if he did. She would be aghast at your neighbourhood monkeys. I shan’t tell her – she would be too upset, I think.

LikeLike

May 12, 2017 at 3:14 pm

It is dreadful. The cruelty and the general shortsightedness. Good for your mother refusing to use poison. Perhaps a compromise solution is to try to use a live trap-and-release method, assuming the rat can be caught and there is a suitable place to release it to?

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 12, 2017 at 3:31 pm

There is always a suitable place is her and my opinion. Far enough away that he can’t just scamper back and isolated enough with enough food that he is content to stay. Sounds like mankind to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 11, 2017 at 6:08 pm

Fascinating article and one that is echoed certainly in Great Britain though I think a little less here in France – certainly in rural France where we are blessed with kites and buzzards, hawks and even vultures amongst other raptors.

LikeLike

May 11, 2017 at 7:01 pm

Thanks Osyth. I hope that is indeed the case in rural France.

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 12, 2017 at 7:58 am

Whilst everyone celebrates (rightly) the victory of M. Macron over his Nazi opponent on Sunday, I have a single concern. In his manifesto he speaks of modernising agriculture. The fact that farming is still so traditional and that pesticides are unheard of in my region along with poisons because the vast community of feral cats and raptors see to keeping the rat and mouse population under control my be under threat and it saddens me greatly. I can only hope that the status quo is maintained but with a population of young people increasingly wanting out of farming and off to the glamorous cities where there is more opportunity, I do fear for the future of the balanced nature I witness with man and beast and wild creatures co-existing at some level.

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 12, 2017 at 9:10 am

I was not aware that agriculture is relatively traditional in France, and it is sobering news that Macron punts “modernising” agriculture. It would be wonderful if holistic and more organic approaches that are gaining traction in some contemporary circles could eclipse commercial monoculture, and if ways could be found to make farming a viable and attractive option for family-based enterprises.

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 12, 2017 at 11:22 am

Exactly. We have friends who have 40 cows and live high up in the Cézallier mountains in Cantal. They are a milking herd and they make cheese. Apart from covering their acreage on quad bikes and using a mechanised milking parlour and the necessary modern equipment for the dairy, they are very traditional. They use no fertilisers but rather recycle the cow dung, they have chickens for eggs and use the poo for fertiliser for the appropriate vegetables all of which they grow themselves for their own consumption. The male calves live a year alongside their mothers in the fields before being slaughtered for veal, the females calve themselves after 2 years and the cycle continues. The bull lives with his harem out in the fields and it is only when the snows are really really thick that they come inside into the barn. Theirs is s simple life and their two sons aged 29 and 31 live and work with them. The only catch is that neither of them (despite being drop dead gorgeous both) has found a wife because the local girls all want to move to the cities. THAT is what needs to be addressed. The fact is that they have to sell their AOC cheese to a government accredited middle man who gives them a pittance per cheese and they have little money to make the house and cottages more appealing for a bride. I am banging the drum for organic here as I ever have. I hope that many will swing behind the movement and stop Macron in his too hasty tracks.

LikeLike

May 12, 2017 at 1:33 pm

I am very interested to hear about your friend’s farm. How humane that the young calves remain with their mothers. Sad that no young women are attracted to this lifestyle. So many issues here! Perhaps the government-to-be needs to address the way farmers get paid for their produce first?

Last week I happened to be talking to the wife of a retired dairy farmer. She said that no-one can survive as a dairy farmer nowadays in our part of the world with less than 3 to 4 thousand cows, and the whole industry is run by a few large national companies.

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 12, 2017 at 1:42 pm

All farmers farm that way in our area … the calves all stay with their mothers, father in tow (and i have film of bulls ‘minding’ the calves to give the cows a break). You are right. In a nutshell the issue is what the farmers are paid. Stop cowtowing (pun intended) to the consumer and stop cheap imports and hey presto bongo (because guess, what? I’m not a rocket scientist) you have the makings of a solution. A better lifestyle for the farmer equals more appealing for the young wanting to move away to uncertainty. I should be president. Or you. I’d vote for you, actually!

LikeLike

May 12, 2017 at 3:07 pm

How fascinating that the bulls play a parenting role when allowed to live more naturally. Sad that so many never get the opportunity.

Thanks for your vote of confidence 🙂 Unfortunately, I don’t think commonsense solutions can prevail when there are so many vested interests. It seems that even the best presidents end up being sort of clearing houses for competing interests. So rather you than me for president!

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 12, 2017 at 3:30 pm

The politics of it all is depressing, you are right. I just hope that good sense prevails. My husband (a Harvard Professor) is of the opinion that investment in the future is best made in the very young. They that will reap the bitter harvest, they that may have it in their hands to turn things in the nick of time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 11, 2017 at 3:58 pm

Oh yes, by the way. Those traps. We tried them all.

LikeLike

May 11, 2017 at 6:58 pm

Did the electronic trap also fail? I had heard that they work well. And the Nooski Trap has a good track record in New Zealand where it was developed to control invasive alien possums.

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 12, 2017 at 7:05 am

To be fair we never managed to track down an electronic trap. And despite our research, we didn’t hear about the Nooski trap. Ours were all off-the-shelf traps recommended by ships or friends. We’ll know next time …. if there is a next time.

LikeLike

May 12, 2017 at 7:18 am

Hi Margaret. Thanks for taking the trouble to reply. I am not sure how widely available the Nooski trap is/was, which is likely why you did not find it when you went to all the trouble of researching how to deal with your troublesome rat. And hopefully there won’t be a next time!

LikeLiked by 1 person

May 11, 2017 at 3:57 pm

I agree with all you wrote about rat poisons. In theory. However, about five years ago, a rat moved in (we lived near a river where they were abundant). Over a period of six weeks we tried everything and built more humane traps than you can imagine (let’s hear it for youtube!). Nothing worked, and the rat became more and more daring, and got into food supplies we thought were well tucked up. We had a grudging respect for his intelligence. In the end, yes, we resorted to rat poison. It died a horrible death, but wasn’t released into the food chain. Given the same situation again, I don’t know what I’d do. The creature suffered, no doubt. But we weren’t wild about sharing our home with a rat. Difficult.

LikeLike

May 11, 2017 at 6:52 pm

It is best if the choices we make are reasonably well informed. Good that the poisoned rat was disposed of safely.

LikeLiked by 1 person